A paper published in Wildlife Research in July 2018, and authored by a team of well-regarded researchers, concluded that Australia has its “head in the sand” regarding pressing health concerns related to lead-based bullets in wildlife shooting. The paper received some attention at the time, yet, two years on that conversation has more or less ceased. To use another well-worn wildlife idiom, are we now ignoring the Elephant in the Room?

Lead shot was phased out for waterfowl hunting South Eastern Australia over a quarter of a century ago, based on scientific evidence about harm and potential harm to wildlife and human health. In July last year, lead bullets were banned for all hunting in the US State of California, following a six-year phase out period. At least thirty States of the USA regulate the use of lead ammunition.

The Californian ban followed lead bullets being identified as a key threat to the endangered Condor. The impacts on birds of prey and carrion eaters are well documented in numerous studies.

Likewise, for humans, the World Health Organisation estimates that as many as 540,000 people have died from lead exposure and it advises that no level of lead exposure is considered safe for humans.

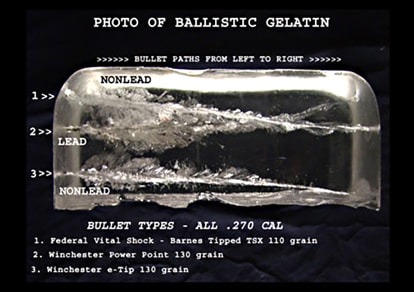

Lead projectiles are ubiquitous because they are affordable and they have great qualities including stability, malleability, rapid expansion and fragmentation. The design qualities of modern hunting bullets have been proven to have provided effective substitutes for lead in both the USA and Europe.

Lead bullets fragment through game meat surprisingly effectively. Studies have shown that hundreds of lead fragments are found in shot game, some as far as forty-five centimetres from the wound channel – how hard do you really trim your venison?

Research has also found consistently elevated blood lead levels in consumers of wild shot game.

More research and study is needed on the impacts of lead bullets in Australia. We have a relatively small population dispersed over a sprawling land mass. What is clear is that this conversation is not going away, the Elephant remains in the room. As hunters, we owe it to ourselves and to wildlife to play a productive and considerate role in that conversation.